This text focuses on electronic navigation applications for small boats. These electronic applications are used to display electronic charts. For concrete examples, I wrote five introductions to different applications: Navionics (Boating), OpenCPN, C-MAP, Savvy Navvy and SEAiq. Below, I detail the elements common to navigation apps generally found on sailboats, yachts and in broader terms, non-ECDIS vessels.

1. Apps automate certain navigation tasks

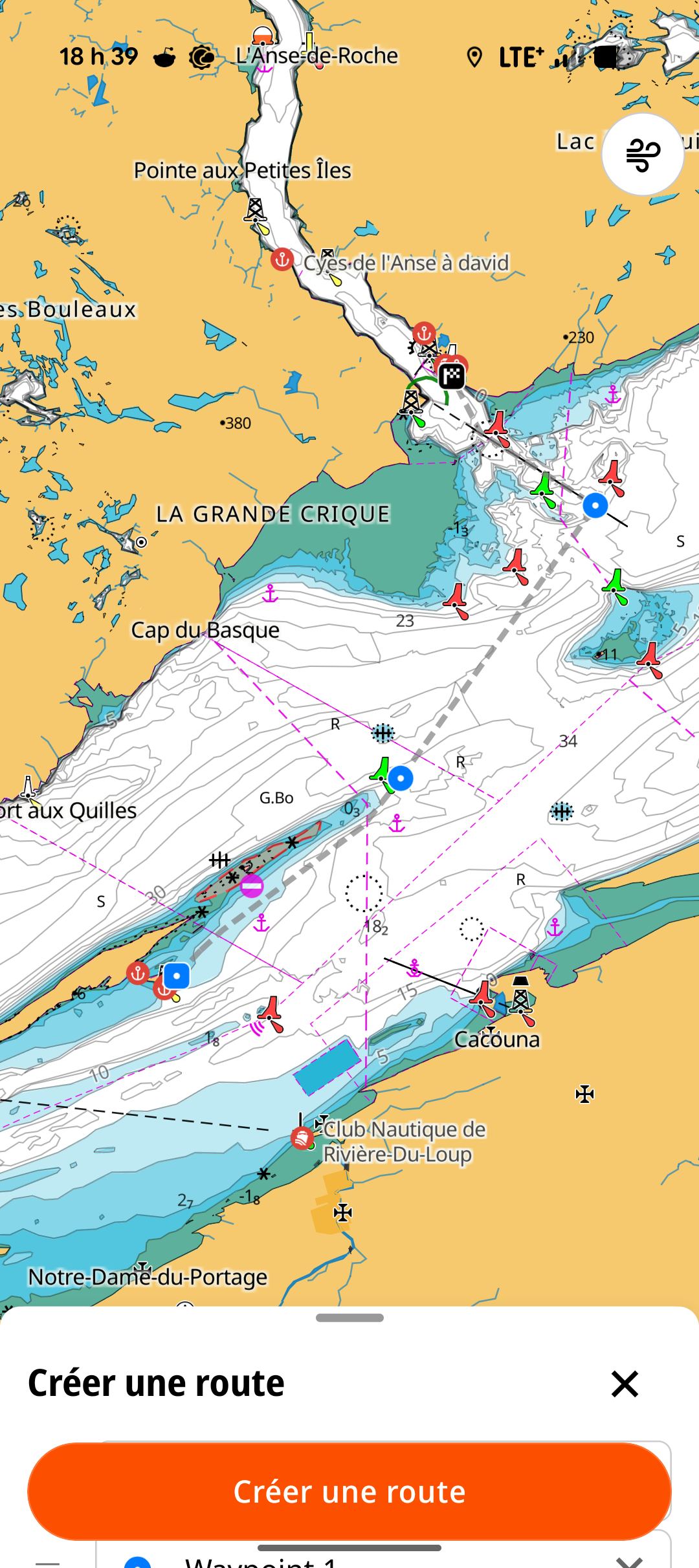

The main advantage of an electronic application is that it automates certain navigation tasks. They can automatically determine the boat’s position and speed; they can build, save and share routes; they can record the actual path taken by the boat; and they even offer assistance with passage planning. In particular, some applications display tide cycles directly. If the application is reliable, it is no longer necessary to calculate tide windows by hand.

Automating these tasks saves time. Less time is spent determining where the boat was. In turn, more time can be spent anticipating where the boat will be, improving navigation safety.

2. You need a computer to use them

Some form of computer is needed to run navigation applications. Sometimes it’s a chartplotter. Popular brands are Raymarine, Garmin or Simrad, but there are others.

However, these computers are relatively expensive ($2,000 or more), and it’s also an established practice to use a cell phone or a tablet computer (e.g. iPad, etc.). These devices are not all equal in terms of use and possibilities. The power source, namely the capacity of the battery, is of prime importance. Also, screen size will be a factor affecting how easy it is to plan routes: the larger the screen, the better it is for planning… but the more power it will consume. To mention two extremes, the Garmin inReach GPSMAP has a screen measuring about one inch by two inches. It’s tiny, but its battery life is of several days. Conversely, a Samsung tablet will have a screen of around 11 inches by 7 inches. It’s bigger, but with a display setting for a bright day, its battery will power it only for a few hours.

For diy-ers, it’s also possible to use a microcomputer, such as a Raspberry pi (and this isn’t something I’ve tested). The advantage is that it is not expensive.

3. Mapping information comes from the government

Whatever is your favorite application, if you are displaying a chart in Canadian waters, the data transmitted by most electronic applications comes from the Canadian Hydrographic Service. Private companies operating these applications pay user fees in exchange for access to chart data.

In this sense, no matter which application provider you choose, you will get essentially the same cartographic information. There may be differences in color or for certain symbols, but the maps will display the same depths, buoys, etc. The main differences are in the way charts are displayed, how charts are updated.

To use an analogy, you might prefer Coke to Pepsi, but within the can, both are mostly water, sugar and carbon dioxide. The differences lie in a few ingredients!

I take the trouble to write “most” applications rather than all, as some may rely on third-party services. If this is the case, you should exercise great caution and assess the quality of the data obtained. It’s possible that the data on third party charts is out-of-date, wrong, or both!

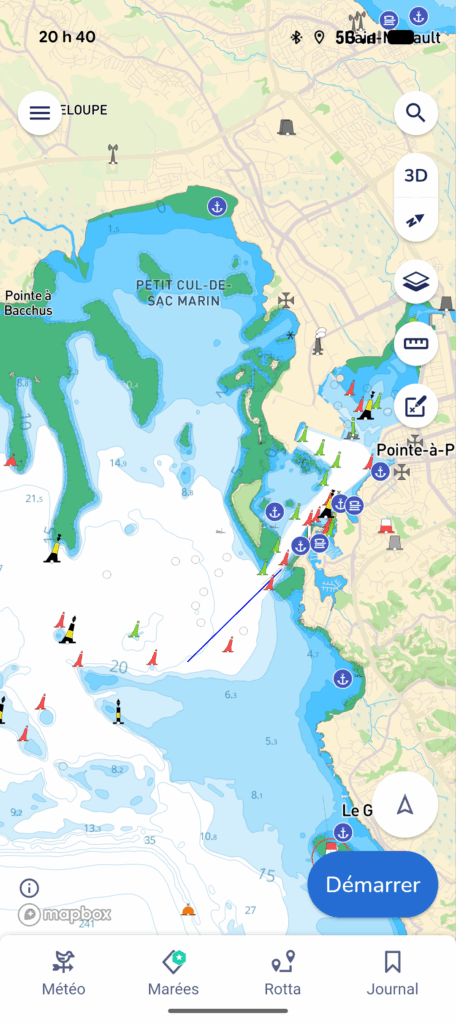

4. Chart symbols vary from one application to another

The International Hydrographic Organization maintains a standard for symbols on navigational charts. Adhering countries ensure that their charts are as close to the standard as possible. This ensures that paper charts look the same no matter what part of the world they cover (and who produced them).

Where there are differences, these standards are recorded in a document called Chart #1. This document is produced by any hydrographic service that produces charts. Below, I show an extract from Chart #1 of the Canadian Hydrographic Service, but it’s also possible to download the same document for France, the UK, the USA or other countries.

Many electronic navigation applications use symbols that differ from the international standard. Some applications even offer the option of configuring the display standards to suit personal tastes. These differences are generally minor, but can sometimes lead to confusion. If you are just starting to navigate with a new electronic application, it is a good idea to familiarize yourself with the tool it uses to explain the symbols on the chart. In this respect, applications differ greatly: some do not display all symbol-related information, while others offer a wealth of detail. The most important differences concern bathymetry, water depth and “natural” navigation hazards (rocks in the water, etc.).

5. The device must be equipped with or connected to a GPS

The device must be connected to a GPS, or have a built-in GPS. Otherwise, it will be impossible to know your boat’s speed and position! Similarly, it won’t be possible to record the actual track your boat has taken. As a result, your electronic navigation application is reduced to a chart display.

It is worth noting that iPads only have built-in GPS on models that include a cellular chip. If you want to dedicate a tablet to a navigation application, you will need to check that a GPS is included with the tablet.

Laptop computers (Mac or PC) allow you to use certain navigation applications (e.g. OpenCPN, SEAiq). As a general rule, computers do not come with a built-in GPS. One practice is to purchase an external GPS that can be connected via a USB port, and then ensure that the application can “see” the GPS. This approach requires configuring the application, the computer or both! Another approach is to connect your computer to your sailboat’s NMEA network, if you have one, and be prepared to do a bit of tinkering. Just keep in mind that a laptop with no GPS will have the same drawbacks as a tablet with no GPS.

6. The application displays the position of the GPS receiver

Your application will display the data received by your GPS receiver. If this receiver is installed on your sailboat, it will intrinsically display the boat’s position and speed. On the other hand, if you’re using a cell phone or a mobile tablet with a built-in GPS, the application will display the position and speed … of your device. The difference is significant if you are walking on your boat (or on the dock) while reading the speed and position information. If you are walking in the direction of the boat, your displayed speed will be the sum of both speeds: yours and that of the boat.

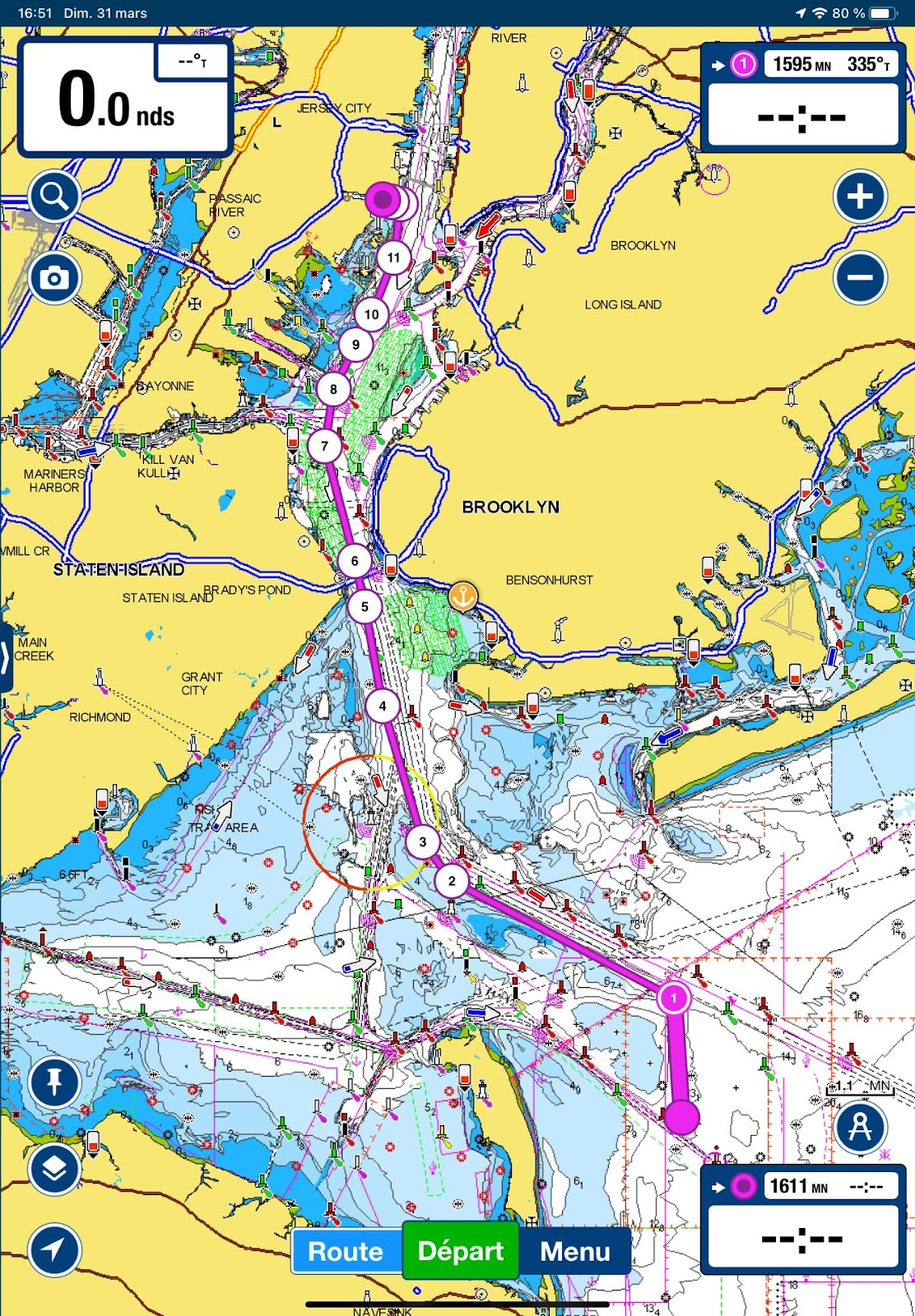

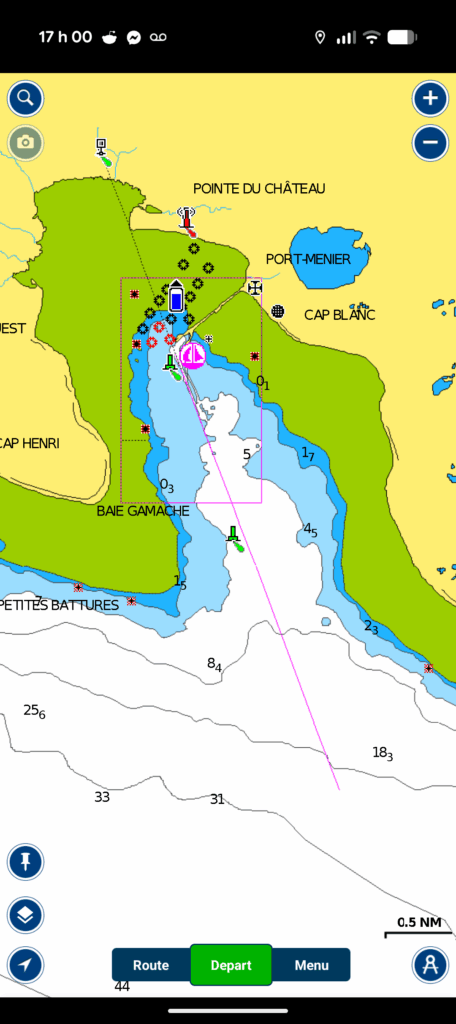

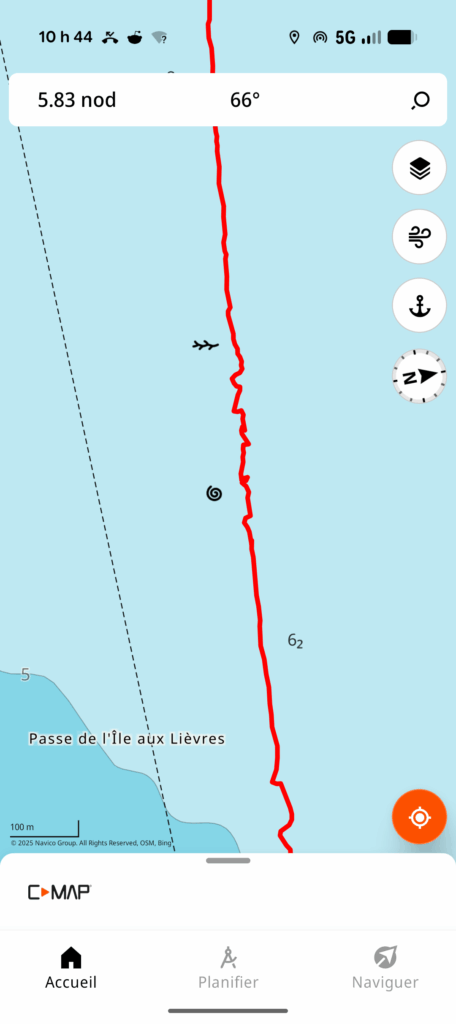

Similarly, the actual track that is recorded is that of the device. The image on the left, a screenshot of the route recorded with C-MAP, clearly illustrates the difference between the two.

The erratic behavior in the middle of the image has nothing to do with the skills of the person at the helm! On the contrary, the zig-zags show the combined effect of the boat and the cell phone recording the course. This phone was in my pocket while I was going back and forth on the deck.

In short, the device measures the position of the GPS receiver. If this receiver moves in relation to the boat, the information will be slightly distorted.

7. No need for cellular data

Most navigation applications do not require cellular data to navigate. You do, however, need to download charts in advance, which you can do with a wi-fi connection or a data plan.

Some applications offer map subscriptions that are less expensive, but do not allow you to download charts. In other words, this type of subscription requires that you sail within cellular reach. Needless to say, it’s not good practice to use these subscriptions for navigation more than five nautical miles offshore.

In an emergency, any device with a GPS receiver will display GPS coordinates without a cellular connection and without an electronic navigation application. All you need to do is download an application that displays longitude and latitude coordinates. Of course, you’ll need to know how to transfer this information to a paper map.

8. It is wise to have redundancy

Portable electronic devices can be lost, dropped in the water, out of power or broken. I’ve sometimes dropped a device in the water, or been unable to charge it because the charging port was too exposed to the rain.

For those reasons, it is a safe practice to have a second device with an application installed, up to date, and with charged batteries. Similarly, it is good practice to bring more than one charging cable, and an external battery to recharge your device.

9. It is wise to bring your own device

If you are sailing on someone else’s boat, the capabilities and status of the chartplotter will be unknown until you are onboard. Electronic devices are subject to repairs and electrical tinkering by others. It is not impossible to experience broken screens, blown breakers or out-of-date charts. If navigation depends on someone else’s electronic device, it is a good idea to bring your own.

10. Legally, you still need paper charts

The USA, France, the UK, New Zealand and Australia recognize electronic applications as acceptable substitutes for paper maps. In fact, neighboring countries (notably in the Caribbeans) are following the lead of the major maritime powers. In Canada, however, this is not the case for recreational boaters.

For pleasure craft, the Navigation Safety Regulations specify that paper charts of an appropriate scale must be carried on board, unless you are familiar with the body of water on which you are sailing. It is important to understand that if you’re sailing repeatedly in known waters, you don’t need charts. But if you’re traveling in new waters, Canadian pleasure craft must have paper charts.

I’m one of those who believes that this regulatory obligation should change, in particular to keep pace with the practice of the vast majority of boaters, and to allow electronic applications. However, this is not yet the case, and if we want to comply with the law, we need paper charts on board (and more generally, nautical publications). To follow the evolution of e-navigation in Canada, visit the Canadian Coast Guard’s e-navigation portal. In particular, the page detailing the government’s roadmap clearly illustrates the challenges involved in the transition to electronic navigation.

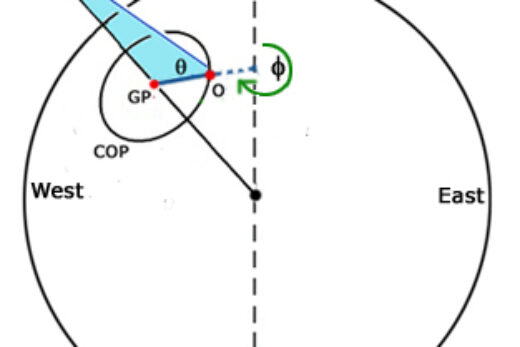

11. You will only see the course and speed over the ground

Unless your navigation app is connected to a compass attached to your sailboat and log, you will only see your course over the ground (COG) and speed over the ground (SOG). Succinctly, this information indicates in which direction the boat is going (as opposed to where it’s pointing) and how fast the boat is going in relation to the ground. If you’re unfamiliar with these concepts, I encourage you to take a navigation course.

With a tablet or cellular device, it is impossible to know your speed on the water, or your drift caused by the current. To estimate this information, you have to do it by hand, or connect your app to the sailboat’s instruments.

12. Two pricing models

Electronic navigation applications essentially provide two services: 1) displaying navigation charts; and 2) providing user-friendly software with additional functions. From the user’s point of view, these two things are almost the same: using the application necessarily implies displaying maps. However, from a production point of view, these services are completely different: the software is produced by a private company, but the charts are produced by the Canadian Hydrographic Service (or another hydrographic service elsewhere in the world).

Some hydrographic services, such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, in the USA) or the New Zealand Hydrographic Service, make their charts available to the public free of charge. In other countries, notably Canada, hydrographic services sell their products to resellers or suppliers under service contracts. This includes companies producing electronic navigation applications.

Because of this difference in production source, companies opt for different pricing models.

Monthly subscription

The first model – the most common – consists of an application that can be downloaded free of charge, but requires an annual or monthly subscription to use a given set of charts. With a single fee, the application covers not only its contractual costs to the Hydrographic Service, but also the application’s development and maintenance costs.

Purchase of software and maps

The second model separates software production costs from chart costs. In this case, you pay for the use of the software, and pay an additional amount if the hydrographic department asks you to pay for their services.

This pricing model is more transparent, because it shows that if the charts are available free of charge, as in the USA, the only costs are for the software. An annual subscription, on the other hand, conceals the fact that some charts are free.

Conclusion

Electronic navigation applications are great tools for automating certain navigation tasks. They do not, however, dispense with the navigator’s obligation to perform these tasks manually, or to plan his routes. Understanding their use and limitations also helps to make them your own. This text, covering a number of general points, covers a wide range of applications often available on small boats or pleasure craft.

For the specifics of each application, please refer to the Learning section of this site. It includes texts on the Navionics (Boating), OpenCPN, C-MAP, Savvy Navvy and SEAiq applications. In particular, it covers how to perform eight essential navigation tasks:

- obtain charts;

- read symbols on a map;

- plan a route;

- save the actual route taken;

- obtain speed and course over ground;

- obtain current and tide information;

- exchange previously created routes;

- plan and execute routes.

They are more practical and focused on practical use.

6 Responses

[…] Prior to reading this text, it is a good idea to reat the introduction to electronic charts and the introduction to electronic navigation applications. Both will help understand this […]

[…] but also to understand their limitations. It is essential reading before using our introduction to electronic navigation applications. You can also read a similar text on the Canadian Hydrographic Service […]

[…] and SEAIQ applications respectively. Before reading this text, it’s a good idea to read the Introduction to Electronic Navigation Applications text, as it applies to all navigation applications. It’s also a good idea to understand the […]

[…] to read the text explaining electronic chart formats. It is also a good idea to read the text about general features of navigation apps. Both are helpful to make good use of any navigation […]

[…] the sailboat’s instruments, such as a tablet or GPS-enabled cell phone. In this respect, the Introduction to electronic navigation applications text, as well as the Introduction to electronic charts text, are good prior reading. They cover […]

[…] Navvy and C-MAP applications. As prior reading, the texts Introduction to Electronic Charts and Introduction to Electronic Navigation Applications cover knowledge required for this […]