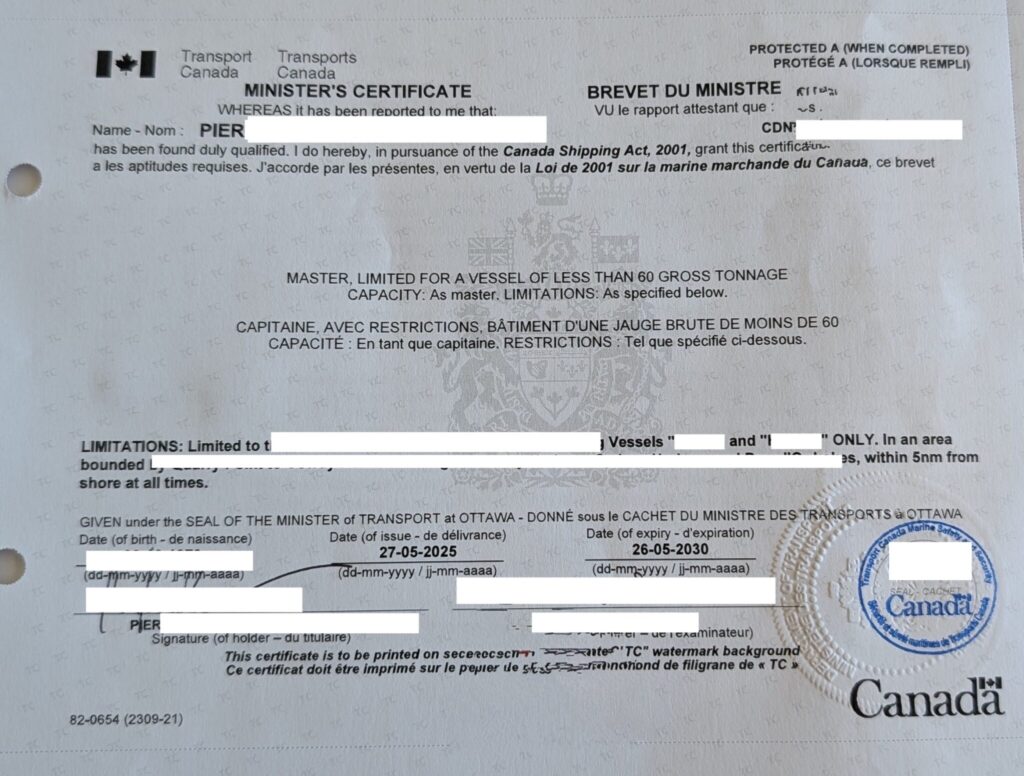

Officially entitled ” Captain, with restrictions, of a vessel of less than 60 gross tonnage “, the “Master 60” is a Canadian professional certificate issued under the Canada 2001 Shipping Act. It entitles the holder to engage in commercial sailing activities. It confers all the powers – and responsibilities – of a captain.

On a beautiful sunny day, with steady winds of 10 knots, I passed the last two exams leading to the issuance of the certificate. I describe below 10 of the realities associated with obtaining it.

1. Certification is boat-specific

The Master 60 certification is boat-specific. It is not universal, and it is not transferable. The boat you designate for the exam will therefore be the boat you can captain. Consequently, the assessor will adapt the pre-requisites and your exam to the vessel in question. A Master 60 exam for a tugboat won’t be the same as for a general workboat, or even a sailboat.

Since I took the exam for a sailboat, it’s important to understand that some of the items below may be different for another type of vessel. In the image above, you can see the patent and the inscription of “limitations”. One of these concerns the validity of the patent for only two sailing vessels (which have been redacted).

2. Prerequisites compiled by Transport Canada

The requirements in terms of knowledge and accumulated sea time are set out in Transport Canada standard TP2293. A minimum of two months’ cumulative sea time is required on a boat similar to the one for which certification is being sought.

Accumulation of sea time is governed by the rules set out in the Merchant Shipping Act. To register, you need a candidate number (the maritime equivalent of a social security number).

Examination requirements include “Chart and Pilotage, Level 1”, “Navigation Safety, Level 1” and, depending on the vessel, other examinations relating to ship construction and stability. The first two tests a candidate’s ability to navigate and find their way around on charts. The second exam assesses knowledge of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (RIPAM).

The need to pass other exams is at the discretion of the assessor, depending on the boat in question. Vessel construction and stability exams are primarily intended for steel vessels, and may not be required for sailboats.

Passing these exams may be a limiting factor in your ability to qualify for certification. The chart and piloting exam requires a good knowledge of coastal navigation techniques. In terms of comparison, you need to have mastered at least the equivalent of Sailing Canada’s intermediate level of coastal navigation, plus a few more advanced techniques. You also need to know how to calculate tide levels. If you use the Voile Canada annotation convention, you’ll need to be prepared to explain it at the end of your exam, as it is less widely used by evaluators, who use maritime shipping conventions.

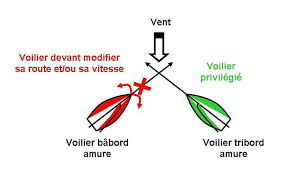

The navigation safety exam consists of 100 multiple-choice questions on priorities on the water, as well as collision avoidance rules. You need to know the RIPAM from top to bottom, including the Canadian modifications and some of the appendices, and be able to apply it in all circumstances.

You also need basic first-aid certification, as well as certification in marine emergency duties. These are separate courses to be taken prior to certification. The marine emergency training course will depend on the commercial activities you wish to carry out on the vessel. In particular, if you intend to carry passengers, the training will be more demanding.

Finally, you must hold a Restricted Commercial Radio Operator’s Certificate (ROC-MC). This certification must be obtained before taking the exam. It’s almost the same as the certificate for pleasure craft, except that it covers the GNDSS system, radio coverage areas and functions specific to digital selective calling.

3. Assessment requires (at least) two practical tests

Certification requires both a practical and an oral examination. The practical exam takes place on the water and resembles any assessment from a sailing course. Perhaps closer to the mentality of the Royal Yachting Association than that of Sail Canada, your assessor doesn’t know you, and will test general boat handling skills: docking, overboard recovery and general maneuvering. You need to have enough manoeuvring knowledge to confidently perform whatever is asked of you. The assessor does not follow a set syllabus.

Nor should you be surprised if surprises “appear” during the assessment. Detached by the assessor, I had to go back and attach a genoa sheet during the exam. It’s nothing particularly difficult to correct, but it illustrates that you’ll be tested on your ability to deal with a few practical surprises once you’re on the water.

The oral exam covers general seamanship knowledge, emergency response procedures (fire, damage, etc.) and general navigation knowledge. You may be asked to tie knots, describe buoy characteristics, or answer general questions about RIPAM. Certainly, you’ll be asked to detail all the safety equipment needed on the boat, as well as its use.

All in all, you should allow half a day for both exams.

4. It’s an assessment… not a course

The title says it all. The assessor… will assess you. He’s not there to tell you what to do, nor to give you a course. You have to come in knowing it’s going to be an exam.

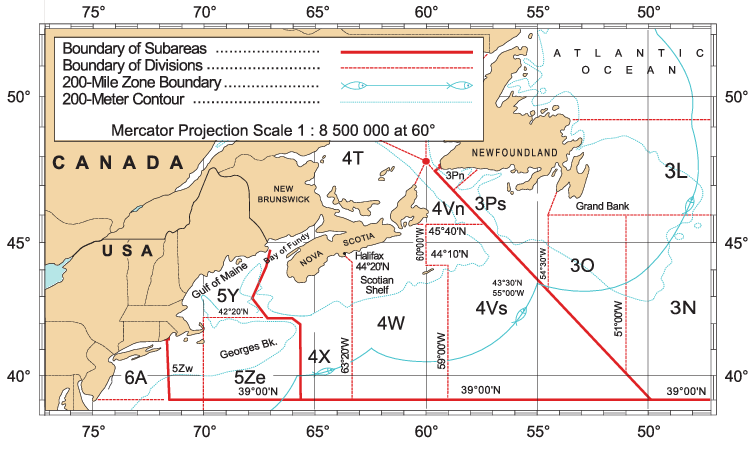

5. The certificate comes with a geographical restriction

The Master 60 license comes with a restriction on the area of operation. It does not, for example, allow international travel. These restrictions may depend on the owner of the boat (if it’s not yours)… or on the insurance company. Geographical restrictions may vary at the discretion of the evaluator

As far as I’m concerned, the patent includes a geographical limitation (redacted in the image) given by cities and by a maximum distance of five nautical miles from the coast. It’s this distance limitation that I find most annoying. If you want to sail commercially on the high seas, you’ll probably need a Captain 150 certificate, or astronavigation exams. Either way, it’s a drastic change from the Yachtmaster Ocean, which has no distance restrictions.

6. The boat used for the exam must correspond to the patent

The boat must be over five gross tons and, obviously, less than sixty. If the vessel is less than five tons, the assessor may refuse you the certificate and redirect you to a Small Vessel Operator‘s Certificate. Similarly, it is not possible to take the exam on a pleasure craft. The sailboat must be registered as a workboat, training vessel, passenger-carrying vessel or other commercial registration. In other words, the certificate not only reflects your skills, but must also be justified by the boat to be used.

7. The boat is also assessed

The assessor will look at everything that relates to his or her responsibilities… including safety equipment… and the vessel’s seaworthiness. For example, during my assessment, the inspector pointed out the absence of a DSC-capable VHF radio on the sailboat. This is a prerequisite for commercial vessels, and he made it clear that it would be a good idea to replace the radio before the next surprise visit. What you need to understand is that the examination is holistic and includes the condition of the boat.

8. You get a robot crew member

You can choose a crew member to help you maneuver the sailboat. However, the assessor clearly specifies that this crew member is an “automaton”, in the sense that he or she cannot take the initiative, suggest maneuvers or draw attention to any problems. He or she can only follow detailed instructions (e.g. to ease/edge, hoist, etc.).

9. Emphasis on safety

Both the oral and written exams focus on safety. The assessor asks a lot of questions about catastrophic situations: damage, engine failure, fire on board, illnesses on board, free surface effect, etc. On the other hand, the elegance of your maneuvers and the trimming of your sails are less evaluated. Unsurprisingly, the assessor will ask you to perform an overboard recovery exercise. The exercise is comprehensive: the evaluator will want to see your technique for bringing an unconscious person back on board. It helps to have a well-thought-out procedure (halyard attached to a shroud, sling under the arms, etc.)

10. Written procedures are required

During the exam, I was asked to detail a procedure for managing an on-board fire during the night. Naturally, I detailed this procedure orally, in great detail. Then the assessor immediately replied: “You’re dead: where can the crew find the fire-fighting plan?” As well as training the crew in emergency procedures, the assessor took the trouble to stress the importance of having a written emergency plan on board for a range of scenarios.

Conclusion

For someone with average sailing experience, the practical test won’t be particularly difficult. I’ve done more difficult practical exams in the past. The difficulty lies more in managing the prerequisites and reinforced emergency procedures that are specific to commercial activities. Personally, I enjoyed the exercise, not least as an introduction to Transport Canada’s practical test mentality. And of course, the certificate confers all the responsibilities and powers of a captain’s title.